- Posted by lvikander

- Category:

- 0 Comments

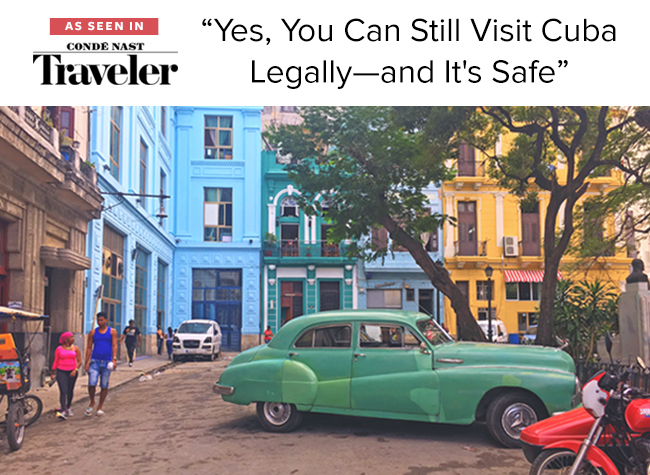

Conde Nast: Visit Cuba Legally

Despite a State Department warning and declarations from the Trump administration, Americans can—and should—be going to Cuba right now.

On Sunday, I flew to a place that the U.S. State Department considers as risky as Pakistan, Russia, or Sudan. In its latest advisory, the agency says that Americans should "reconsider travel" to Cuba due to "health attacks directed at U.S. embassy employees" in Havana. Maybe that's why there were only 15 other passengers on my flight, a JetBlue nonstop from New York's JFK that could seat up to 150.

Not everyone agrees it's dangerous. Canada, for one, advises its citizens to simply “take normal security precautions,” the same thing they say about the U.S. And the U.K.'s Foreign and Commonwealth Office says that “most visits to Cuba are trouble free" and "crime levels are low and mainly in the form of opportunistic theft." But for Americans, Cuba has swiftly turned from an It Destination just two years ago to a place to be avoided (again), after repeated blows to its reputation in recent months: First, President Trump said he’d be "canceling" the Obama-era regulations that spurred huge interest in independent travel to Cuba. Then, Hurricane Irma made landfall. (The storm caused some damage to already shaky infrastructure, but nothing on the scale of what we've seen in Puerto Rico or other parts of the Caribbean.) Next, after reports of those “health attacks”—and U.S. embassy workers in Havana reported experiencing "hearing loss, dizziness, headaches, fatigue, cognitive issues, visual problems, and difficulty sleeping"—the State Department warned broadly against travel to Cuba. Finally, the Trump administration enacted relatively minor changes to travel regulations in November that made it more difficult than ever to parse how—and if—it’s possible to visit Cuba as an American.

“These headlines, unfortunately and without merit, had a cooling effect on the industry,” said Tom Popper of the tour operator InsightCuba on Monday. “President Trump’s announcement left many thinking that travel was over,” Popper said, but "Americans can visit in much the same way they were able to before.”

Popper delivered these comments at the first-ever "Cuba Media Day" that his company had organized in Havana. I’d flown in to hear from both U.S. and Cuban tourism officials during the day-long event, which promised to clear up the admittedly confusing changes to the travel rules. Among the attendees were Jose Bisbe York, president of Viajes Cuba, a part of the Cuban Ministry of Tourism; Martha Pantin, of American Airlines, which has just asked the Department of Transportation for 17 additional flights a week between Havana and Miami; and Michael Goren, of Group IST, which organizes small-ship cruises around Cuba.

Let’s get the obvious out of the way: All these organizations have a vested interest in getting more people to visit Cuba. And they’re likely to focus on the upsides—it’s safe; it’s a short flight from the East Coast—rather than the downsides, like its crumbling infrastructure and the fact that some tourism dollars do go to the government. But these companies also wouldn’t be banging the drum if it were truly a bad idea for visitors to come.

Thus, Cuba Media Day. “There are more ways to go than there were a few years ago,” Popper said, mentioning not just well-known people-to-people tours but also cruises as an easy and legal way to see the country. It's true that the rules governing travel to the country changed on November 9, 2017, said Lindsey Frank, a lawyer with Rabinowitz, Boudin, Standard, Krinsky, and Lieberman, a firm that specializes in parsing Cuba sanctions. “Part of the problem with the rhetoric is that it’s created a lot of misunderstanding,” Frank said during the event. “Individuals can still travel on their own, just like the former people-to-people programs as long as they stay in casas particulares," or privately run guesthouses, "and they engage in the same kind of people-to-people programs that they were doing in droves prior to the previous regulations.” All that's changed, Frank said, is that this sort of trip is now categorized by the U.S. government as "Support for the Cuban People Travel" rather than "People-to-People Travel."

In plain English, that means that it's still possible to book your own flight to Cuba, stay in a casa particular, and put together your own itinerary, as long as it includes hanging out with Cuban people and patronizing privately owned businesses like paladares (restaurants) rather than government-controlled shops—which is exactly the sorts of stuff most travelers do on any trip anywhere. “In sum, there have been very few substantive changes to the regulations. It very much remains a legal place for U.S. travelers.”

But is it safe? No doubt, the State Department’s warning is nerve-wracking. Yet Cuban tourism officials point to the more than 4.5 million visitors that came to the island in 2017 as proof of the destination’s overall safety. “There are so many places to choose from around the world,” said Bisbe York, the Cuban tour operator. “[But] 39.6 percent of our clients are repeaters,” he said, meaning they’re back for a second or third trip. “About 20 percent of our guests come with their families,” a sign of its safety, Bisbe York said, “and 96 percent of our clients would recommend the destination. You wouldn’t recommend to your friends or family a place where there’s some kind of risk.”

I certainly didn’t feel any, though my own visit to Havana was an admittedly brief two-night stay. In fact, while I was in Cuba, the U.S. State Department emailed the Miami Herald to report that “since September 29, the Department of State has been contacted by 19 U.S. citizens who reported experiencing symptoms similar to those listed in the travel warning after visiting Cuba." That same day, at the landmark Hotel Nacional, one of the properties specifically listed by the State Department as one to avoid, it was largely business as usual, with foreign guests smoking cigars at the Galería Bar and sipping rum drinks on the lawn. Later that night, in Old Havana, crowds of cruisers from the Holland America Veendam were pounding mojitos at El Bodeguita del Medio, a handful of New Yorkers were ordering half the menu at the paladar El del Frente, and the son Cubano band was killing it for a nearly full house at Bar Monserrate, just down the street from the always packed Floridita, which bills itself as the birthplace of the daiquiri.

And here’s the crazy thing: Going to spots like these counts as “support for the Cuban people,” one of the still-permitted categories of travel to the island, as long as you say it does. “Travelers can determine on their own whether or not they meet the [U.S. government] requirements and just go,” says Frank, the lawyer. But, I asked the Cuba Media Day crowd, won’t the government come asking about the details of your trip? “I’ve never, in my experience, heard of anything but innocent questions,” Frank said, like when and where did you go, upon a traveler’s return to the U.S. Some other experts said the subject of Cuba came up in interviews when applying for Global Entry but, again, “it’s always innocuous,” Michael Goren said. "Nobody cares," one insider told me in the lobby of the Meliá Cohiba hotel, as he was running to catch his non-stop flight to Fort Lauderdale. And besides, he continued, how could you possibly check every one of the 650,000 or so Americans who came back from the island last year?

“There are always two sides to Cuba travel regulations,” Popper said. “There’s perception and reality. Perception can be more damaging, and that’s what we’re facing right now.”

Written by: Paul Brady

Article courtesy of Conde Nast Traveler